In March, I was driving around western Slovakia surveying an underground gas storage facility, planning for a day tour of gas facilities with Martin Hojsik, a senior representative of the Renew party in the European Parliament. It was grey, and a couple degrees above zero, with a biting wind. I was on the hunt for methane.

Then I heard it. Plunk-phssshh…plunk-phsssshh…plunk-phssshh. Every five seconds. I found a field full of gas-driven pneumatic pumps at wells used for underground gas storage.

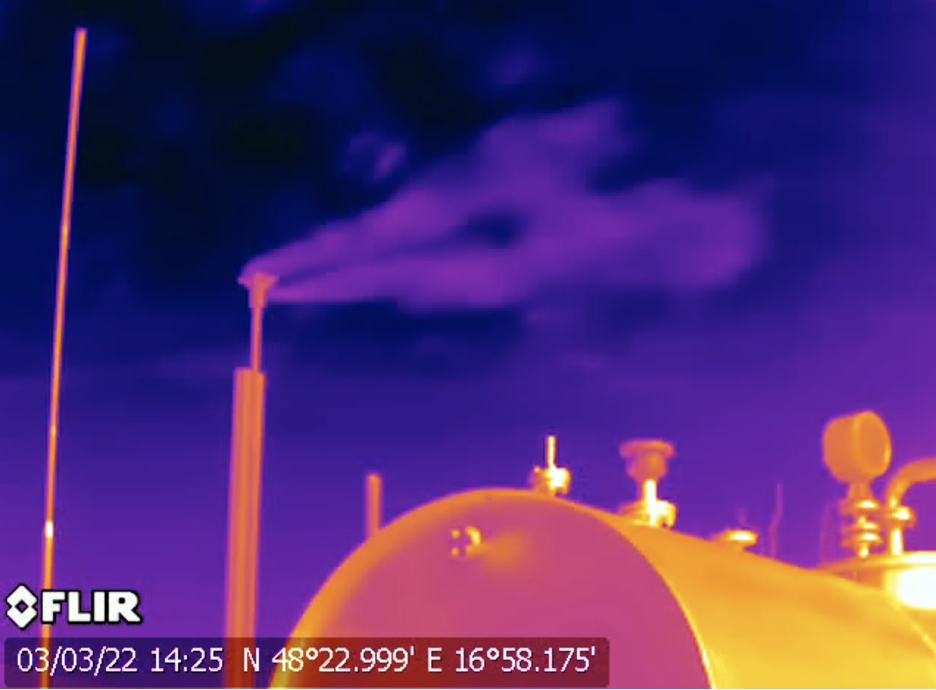

These gas-driven pneumatic devices might be small, but the beasts pack a punch when it comes to methane emissions. They come in different shapes and sizes and are generally used where there is no electricity. They utilize the gas pressure from the reservoir or the well to control the temperature and pressure in the equipment or to pump liquids through the system. Once the gas is used, it’s dumped into the air—this “intentional venting” is one of the largest single sources of methane emissions in the oil and gas industry.

In the US, there are more than 140,000 pneumatic pumps and 1,750,000 pneumatic controllers across the country. Pumps are typically used to inject chemicals into wells and pipelines, whereas controllers are used to control levels, temperature and pressure of the gas and liquids. According to the official U.S. GHG Inventory, pneumatic pumps and controllers release 2.2 million metric tons of methane each year. We don’t know how many are used in Europe because there are no publicly available equipment inventories – one of the many data gaps we’re pushing to resolve with EU-wide legislation.

This pneumatic device is a chemical injection pump. It is designed to inject methanol, a chemical, into a fossil gas pipeline to prevent the cold winter temperatures from creating liquids and condensates. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, a chemical injection pump releases 1.5 tons of methane each year. The EPA estimates that there are 123,000 chemical injection pumps in operation in the U.S. oil and gas industry—that’s 187,000 tons of methane a year – as much as 4 coal-fired power plants.

Gas-driven pneumatic devices are an old technology that unnecessarily wastes gas. They can readily be replaced by air driven pumps or electric pumps.

The next day I took Martin back to the field. We spent the morning talking about the need for strong equipment standards. The Commission’s methane proposal lacks regulations on this type of equipment. This equipment falls into the category of venting-by-design: oil and gas equipment that during normal operations vents gas to the atmosphere. Without a clear equipment standard requiring the use of lower- or non-emitting equipment, companies will be free to continue to use outdated, high-emitting equipment. Examples of strong policies include recently finalized standards in the U.S. states of Colorado and New Mexico, which establish schedules for companies to replace old, venting equipment with modern zero-emitting equipment. This is a major problem and can only be solved by establishing specific equipment standards for equipment such as storage tanks, compressor seals, pneumatic equipment, and dehydrators.

We filmed some short videos discussing the issue and the need for tough methane regulations in the EU. Martin has been one of the most outspoken proponents of methane action at the European level – I was glad to get him into the field so he could see the problems first hand.

After the day was done, I dropped Martin off in Bratislava, grabbed my car, and headed to the mountains. Despite the lack of snow in the Alps this winter, the Tatras had actually received quite a bit. It was exciting to explore new terrain on skis after a satisfying week hunting methane.