In July 2022, we went hunting for methane in Spain.

Although our focus was on the liquid natural gas facilities that have become a centre of attention for Europe’s energy system, we could not ignore a short detour to the only onshore commercial oil field in the entire Iberian Peninsula. The Ayoluengo oil field was discovered in June 1964 and began production in 1967. During its 50 years of activity, the field produced 17 million barrels of oil. The field was decommissioned after the last barrels were extracted in 2017 so now the oil wells form part of the ‘Oil Trail’ of Sargentes de la Lora, a 12 kilometres walk built to help visitors discover the industrial history of the valley.

Clean Air Task Force and Ecologistas en Acción, equipped with an optical gas imaging camera designed to detect methane, travelled to the oil field, and visited 9 wells. We documented emissions at 5 of them. We were curious to see what we could discover in this unusual Spanish valley.

Despite being inactive for years, some for decades, many drilling sites were still leaking gas

Oil wells commonly leak methane and other hazardous gases during drilling and exploitation because gas, called associated gas, is found with deposits of petroleum, either dissolved in the oil or as free gas caps above the reservoir.

When a well goes dry or is not financially profitable, its operator moves on, but these polluting gases can be found at inactive oil wells where it leaks even after they are no longer operational. Research shows that idle, orphaned, and abandoned oil wells are a growing source of methane pollution. Estimates in the United States alone show that emissions from these wells account for 0.3 million tonnes per year of methane, or 2.5% of the total emissions from the oil and gas industry, according to the 2020 Environmental Protection Agency inventory of greenhouse gases.

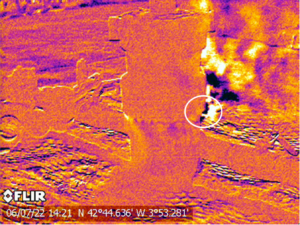

Unknown abandoned well

Only the wellhead remains from this old oil well. Using our IR camera, we observed continuous leaking of methane emissions.

Some wellheads are monitored, but this is not enough

When they are no longer producing oil and gas, wells must be properly closed and plugged. Before filling the well, the operator needs to remove obstructing material (the pump, pipes, rods, etc.) and rainwater. Then, plugging materials, a mix of sand, gravel, clay, bentonite and cement, depending on the type of well, are pumped into the well to make it effectively hermetic and water-proof. A properly plugged well protects the ground, water and air from contamination.

In addition, abandoned and orphaned wells must also be actively monitored to ensure they are not emitting gas, and that should be included in a solid leak detection and repair program. In the case of Ayoluengo, we observed that the operator was regularly checking the wells, small white cards testified for these controls. However, this is not enough. We could find gas escaping from the same old wellheads that were “checked” and “fixed” by the company. One common scenario is that the operators do not have the suitable equipment to monitor the wells and identify clearly what leaks and what doesn’t.

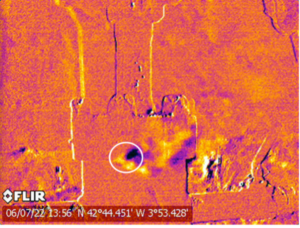

Monitored inactive well n°14

This old well is clearly monitored: the gauge and the handle have been replaced recently. However, when we look at it with our infrared camera, methane pours out continuously.

Tourists can visit the wells even though toxic fumes are coming out of them

Methane is the main compound of the gas we use to heat our homes. While methane is not toxic, it contributes greatly to formation of ground level ozone which can lead to premature death due to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, other toxic gases and hazardous air pollutants, including benzene, ethylbenzene, are commonly emitted from leaky oil and gas wells; some of these chemicals lead to and are directly associated with increase rates of cancer in nearby communities. We provided a more detailed analysis in our study, Fossil Fumes: A Public Health Analysis of Toxic Air Pollution From the Oil and Gas Industry, showing that communities living near oil and gas facilities face heightened health risks related to pollution. Even if the wells are not active anymore, they can keep releasing methane and other associated gases if they were not properly closed, which could be hazardous for human health.

In Ayoluengo, it was common to find oil spills around the inactive wells, where blowouts had occurred. Spills can become a safety concern for unaware visitors. Even, some of the inactive wells were leaking a brine solution onto the ground. The brine, or produced water, is a by-product of the oil and gas production and is composed of groundwater, injection water, oil with high concentrations of salt. When spilled in the ground, this brine solution contaminates the ground, affects the quality of the soil and pollutes vegetation, and can increase levels of radon, a known carcinogen, in the groundwater.

Abandoned well n°20

One of the abandoned oil wells. There were oil spills around the wellhead and methane was pouring continuously from the wellhead. It is one of the stops along the 12 kilometres Oil Trail.

There are only 52 onshore oil wells in Spain and yet, we found methane and other harmful gases polluting the water and the air. Think of the million wells that are emitting associated gas worldwide. In the United States alone in 2018, there were more than 3.2 million abandoned oil and gas wells. This number will continue to grow as the world transitions to newer and cleaner sources of energy.

We do not know the total number of abandoned wells in Europe. The oil and gas industry in Europe dates back to the 1850s. The issue of abandoned and unused wells is complicated by the difficulty in identifying which companies own them or are responsible for them. In some cases, due to the way these wells were decommissioned, no owner can be identified and held accountable for the emissions and the measures needed to address them.

A separate program on methane mitigation for abandoned wells should be established at the EU level to ensure all these wells are identified, sealed, and monitored. Such a program could lead to substantial reductions in methane emissions from abandoned wells as well as employment opportunities. Such measures were included in the European Commission’s methane regulation proposal of 2021.

The fact that we can find evidence of uncontrolled methane pollution even on a tourist trail in rural Spain should be a wake up call to legislators: this is an issue policymakers have to get to grips with as soon as possible.